Massive ‘Ike Dike’ to defend Texas coast awaits federal funds

6 min read

In September 2008, a few days after Hurricane Ike devastated the island of Galveston and the Texas Gulf Coast, Texas A&M University Professor William Merrell had the idea for what was later dubbed the Ike Dike. “It turned out to be based on a lot of Dutch techniques, but we didn’t know that at the time,” Merrell said of his plan to create a system of barriers along the spine of the Texas coast to protect against storm surges. “We conceived of it as a way to protect the region by strengthening the coast.”

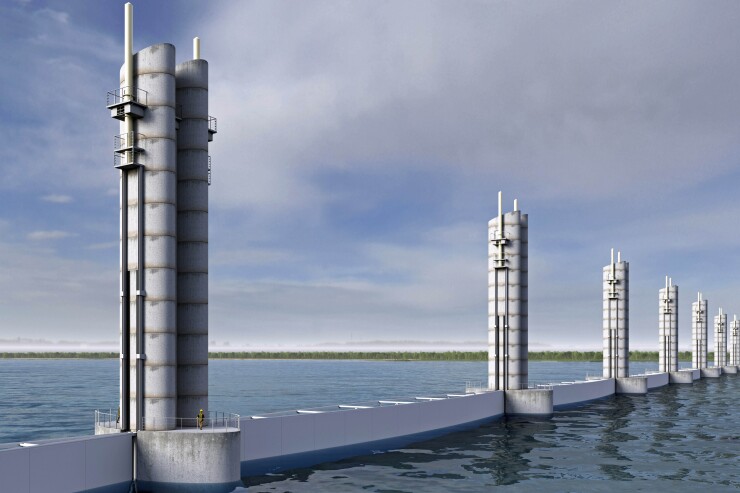

Nearly 16 years later, after a six-year, $20 million federal study, the Coastal Texas Program is poised to become the largest civil works infrastructure project undertaken to date by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The program won formal federal approval last December when President Joe Biden signed it into law as part of the Water Resources Development Act of 2022. The law authorizes the corps to begin to implement the plan once — and if — federal funding is appropriated. With a price tag hovering around $57 billion, it would mark the largest civil engineering project undertaken by the corps to date.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

In the wake of a rising number of extreme storms, coastal communities like the Texas Gulf Coast are trying to figure out how to protect themselves from storm surges, flooding and rising sea levels, and how to pay for that protection.

The largest physical piece of the Coastal Texas plan are the “Ike Dike” sea gates that would remain open during normal weather and close during major storms. Similar sea gates and barriers are already in place in several spots around the country, but the Lone Star State project would mark the largest federal investment so far.

The corps is pursuing an elaborate surge protection plan in New York and New Jersey that carries a $53 billion price tag. The plan has yet to be authorized by Congress.

After Hurricane Katrina, the corps built a $14.5 billion system of levees, gates, walls and pumps around New Orleans. There are hurricane barriers in New Bedford, Massachusetts; Providence, Rhode Island; and Stamford, Connecticut.

Across the U.S. and globally, where gate systems protect areas of the Netherlands and cities like St. Petersburg, the projects are “all a little different and customized, but it’s essentially the same concept – it protects against the surge,” Merrell said.

The Coastal Texas plan is touted as a multi-layered system of defense, with the gates combined with a miles-long system of dunes, reinforced sea walls, elevated beaches and ecosystem restoration features along the Texas coast. Like the New York barriers, the Gulf Coast project is built to withstand a 100-year storm event.

“Hurricane Ike is the biggest reason for this project but Hurricane Ike, while it killed 74 people and caused billions of dollars of damage and significant economic harm, Hurricane Ike missed Houston,” said Lt. Col. Ian O’Sullivan, the corps’ deputy commander of the Mega Projects Division.

If the hurricane had hit 30 miles to the south, “we would have seen 5,000 people die and significantly higher numbers of damage that we would have been recovering from,” he said. “So number one is protecting the people of Galveston and Houston and this region from that kind of impact.”

The project would also protect the Houston Ship Channel, which is part of the largest petrochemical complex in the U.S. and the economic engine of the Texas coast.

Texas accounted for 42% of the nation’s crude oil production and 27% of its marketed natural gas production, and has the most crude oil refineries and the most refining capacity in the country. Texas ports export 94% of the nation’s crude oil, more than 70% of its refined petroleum and more than 70% of its organic chemicals, according to the Army Corps’s Coastal Texas Protection and Restoration Feasibility study.

A direct storm hit to the complex could disrupt the national energy supply, said Brian Harper, director of civil works at the corps’ Regional Planning and Environmental Center. Many of the petrochemical facilities are somewhat “hardened” against extreme weather, but the Coastal Texas plan would add “an extra layer,” in part by protecting the local population, many of whom work at the facilities and are the industry’s “biggest vulnerability,” Harper said.

The financing plan calls for the federal government to cover 65% of the cost with the two local nonfederal partners, the Gulf Coast Protection District and the Texas General Land Office, paying for the remaining 35%. The local partners would also kick in the estimated $150 million in annual operating and maintenance costs.

The Texas Legislature created the GCPD in 2021 to oversee all restoration and resiliencies plans for the upper Texas coast. The district covers five counties and has the power to levy an ad valorem tax. But voters would need to approve the tax, and so far the district’s board has no plans to ask them, said Executive Director Nicole Sunstrum.

“At this point the board has no interest in that,” Sunstrum said.

Nicole Sunstrum

The Legislature in June passed a general appropriations bill that provides $550 million to the GCPD, which will be used in part to launch the initial phases of the Coastal Texas program.

“Right now we are completely state funded and meet all of our obligations from the state,” Sunstrum said.

In contrast to the state support, the U.S. House Appropriations Committee in July opted not to approve a $100 million funding request from Galveston Republican Rep. Randy Weber.

Appropriation efforts will continue, and Sunstrum said funds from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and disaster supplemental funding mark additional avenues. Federal funds may also be appropriated in smaller amounts over the years.

The GDCP is “communicating with our congressional federal sponsors and the corps and our congressional delegation so they know where we are and what the needs are,” Sunstrum said.

The project’s timeline is “dependent on when we get federal funds, which will let the corps really begin,” Sunstrum said. “There are a few things the district can do in advance, but really to see big steps we need the federal funding.”

Even if the funds are appropriated and the project gets built, the Texas Gulf Coast remains vulnerable to another set of climate change-related problems: rising sea levels, said William Sweet, an oceanographer with the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration and lead author for the U.S. Interagency Sea Level Rise Task Force’s 2022 report.

After the Mississippi Delta region, the Texas Gulf Coast is the country’s second-most vulnerable area to rising seas, Sweet said. Levels are rising by about one inch every five years, with certain areas rising at one inch every two years.

On that trajectory, the sea will rise by “a foot and a half by 2050 in that region,” Sweet said.

“A variety of impacts are going to increasingly get worse as sea levels rise and some of the protection against storm surges will help but it’s not going to be a failsafe solution,” he said, adding that the corps’ mission with the project is “not to save Galveston from sea level rise, it’s to protect Galveston from storm surge.”

Rising sea levels require a separate set of solutions and financing plans, Sweet said.

“The Galveston Bay area is not alone in the problems they’re facing,” he said. “What we’re seeing is that typically the solutions are found and funded locally, and it’s going to reflect what the communities themselves find is important.”