Gov. moves to address healthcare challenges in rural Wisconsin

6 min read

To address concerns about a healthcare shortage in western Wisconsin, Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers on Feb. 28 signed a bill that made available $15 million in healthcare grants to hospitals to help them provide services.

The $15 million — which Evers, a Democrat, urged the state legislature’s Republican-controlled Joint Finance Committee to release immediately — comes amid a spate of

“It can be tougher for critical access hospitals, which are the smaller hospitals in rural areas,” said Richard Ciccarone, president emeritus of Merritt Research Services. “If you look at the three groups, the other two are health systems and then general acute. The general acute are basically the independent hospitals that are more like your traditional hospitals, and they can be in large or small cities or towns.

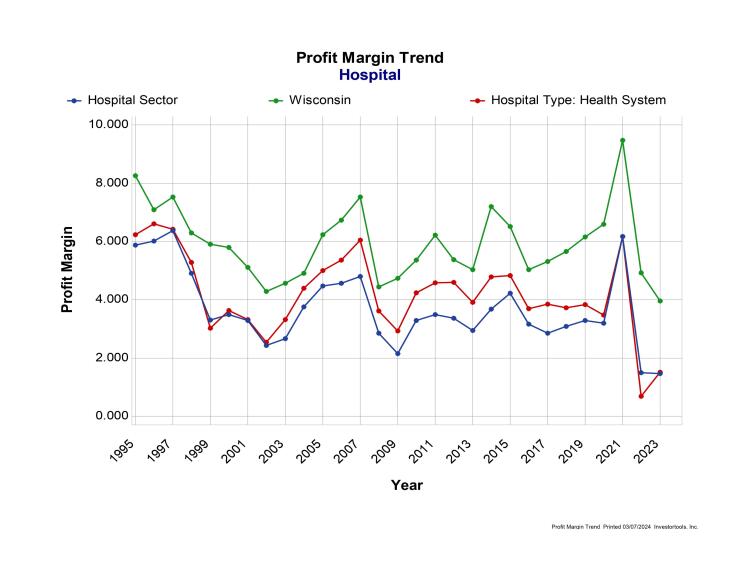

“Overall, what you’ll find is that Wisconsin hospitals are doing better on the total profit margin trend than the sector as a whole,” he added. “But if you just look at critical access, they’re not doing as well in that area.”

Merritt Research Services Investortools

The Joint Finance Committee has not acted on Evers’ request to release the grant funding, said Jon Dyck, supervising analyst at the Legislative Fiscal Bureau, which provides staffing for the Joint Finance Committee. It has not scheduled any meetings on the request, either.

In January, Springfield, Illinois-based Hospital Sisters Health System (HSHS) and Eau Claire, Wisconsin-based Prevea Clinic, a physicians’ primary care network,

HSHS cited “prolonged operational and financial stress related to lingering impacts of the pandemic, inflation, workforce constraints, local market challenges and other industry-wide trends” as reasons for the closures in a

“Our operations in the region have struggled for the past several years due to a mismatch in the supply of and demand for local health care services,” Damond Boatwright, president and CEO of HSHS, said in a statement, adding, “an agreement with a suitable partner did not work out.”

The health system has $57.7 million of Series 2017A health facility revenue bonds outstanding, according to postings on the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board’s EMMA website, with maturities of

Pascaris said the system’s locations in western Wisconsin are in “markets where there are some competitive alternatives.” He added, HSHS “has been working hard to find their footing in terms of their operating performance, and they are making a lot of difficult choices to get back to that sound position.”

Merritt Research Services Investortools

The governor’s office stressed the importance of the $15 million to help fund healthcare in western Wisconsin, and noted the Joint Finance Committee has now twice failed to include it on meeting agendas since the governor signed the bill,

“Western Wisconsin faces serious challenges stabilizing healthcare access across the region, and the critical resources we can use to help are sitting in Madison because Republicans won’t release them — that’s breathtaking,” Evers said in a statement Monday. “I’m once again urging Republican lawmakers to do the right thing and release these funds immediately so we can get to work addressing real and pressing challenges facing our state.”

In his 2023-24 biennial budget proposal, Evers included funds for Medicaid expansion, but the Joint Finance Committee removed them. It was not the first time Evers had tried to sign Wisconsin up for Medicaid expansion and the governor’s office said it remains a top priority for the next legislative session.

Expanding Medicaid would extend health insurance to 30,000 uninsured Wisconsinites and would enable the state to draw down $2.2 billion in federal funds over the biennium, the governor’s office said.

The state would save $1.6 billion as a result due to an enhanced federal match rate for childless adults and a five-percentage-point increase in the federal matching rate for the entire Medicaid program for the first two years after the state opts into the expansion.

“It’s a contentious policy,” said Markus Bjoerkheim, a fellow at the Open Health Project at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center, a nonprofit think tank that favors free markets. “The hope was that people would seek primary care and preventative care more, and that would reduce visits to the ER.”

But, he pointed to research — such as a 2016 study in the

“If you give more people more generous insurance, they actually use the ER more rather than less,” Bjoerkheim said. “There are other studies showing that this increases wait times in the ER and increases other problems with regard to access.”

Proponents of expansion argue that broader Medicaid coverage reduces the financial strain on local hospitals, because there are fewer uninsured patients showing up for emergency care they can’t afford. To maintain their tax exemption, nonprofit hospitals are required to treat patients in their emergency rooms

They “are right on that point,” Bjoerkheim said. “The best papers on this show that a lot of the benefits to expanding go to physicians and hospitals in terms of being paid more for care.”

In

“Studies also point to evidence of reduced racial disparities in coverage and access, reduced mortality, and improvements in economic impacts for providers (particularly

Merritt Research Services Investortools

Dyck of the Legislative Fiscal Bureau noted, Wisconsin “differs from the other non-expansion states in that it does provide Medicaid coverage to both parents and childless adults up to 100% of the federal poverty line,” whereas “other non-expansion states provide no coverage to childless adults, so they tend to have a higher percentage of uninsured adults than Wisconsin does.”

Medicaid or no, Fitch Director Madeline Tretout, who analyzes three healthcare systems in Wisconsin — two healthy and one struggling — suggested the divide among providers is ultimately a cultural one.

“There are certain providers that just seem to have come into these challenges with a really good culture of cost controls, and they were able to really lean on that and dig in a little deeper and really maintain decent performance,” she said, referring to pandemic and post-pandemic challenges. “They didn’t have this lag of what do we need to do now?”

Some hospital credits in Wisconsin still deserve to be bought, noted Ciccarone: “Just because they don’t have the Medicaid expansion doesn’t mean you should write off hospital bonds in Wisconsin.”

Indeed, Merritt’s data shows that even on an operational basis, Wisconsin healthcare providers tended to do better than the national average, all the way back to 1995.

“It’s difficult in this country, in some cases legally, but also just culturally, to close a hospital, or even clinic operations,” Pascaris said. “Most not-for-profit health systems in this country are mission-oriented … but as the old saying goes: ‘No margin, no mission.'”