Letters to Evan Gershkovich, my friend in a Moscow jail

5 min read

It costs 20 roubles per page to write to my best friend, 65 for the envelope, 75 more so he has the option to reply. Last month, we were chatting on a beach. Now it’s letters to Lefortovo prison, and a quiet prayer that he will receive them soon.

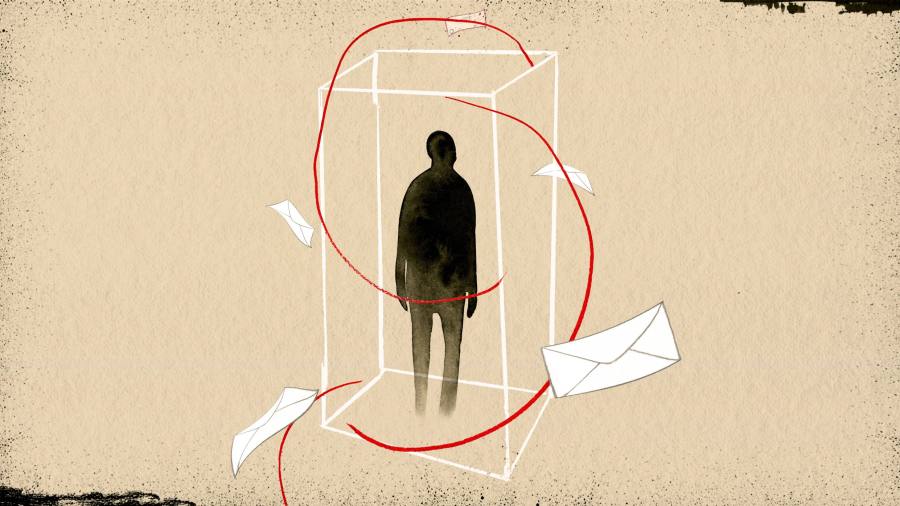

Evan Gershkovich, an American journalist for the Wall Street Journal, was arrested in Russia on March 29 and placed in a Moscow jail. I could write that sentence 100 times and it would not seem any less absurd. Evan has been taken hostage by the Russian state. Espionage: that is the excuse it gives for sending a group of plain-clothes thugs to grab our funny friend and push him hooded into a car; that is the reason why he is now forced to sit in a cell, trapped, alone, and waiting.

As the next chapter in his story, it seems cruelly apt. For years reporting in Russia, Evan chronicled a country descending into darkness and absurdity at an ever greater pace. He arrived in Moscow in late 2017, just in time to see Vladimir Putin re-elected with his biggest landslide yet. I arrived around the same time, to take up my first job as a reporter on the ground.

We’d both grown up far from Russia, but speaking the language at home. Tied to the country in our own complicated ways, we were conscious of its painful past, but hopeful, one way or another, for its future. With two other friends, we chased the same stories, learnt the ropes. Evan loves journalism not just as a profession but as a craft. He’d reel off the names of great magazine writers, knew their best stories from decades back, which we’d then rush to find.

In Moscow, the darkness was present from the start, and quickly became normal. One of the first times I met Evan was at a night hosted by Russian journalists in a tiny basement bar; the DJ was a reporter who’d just recovered from being stabbed in the neck by an assailant in her radio studio.

Summer weekends were spent covering the regular mass protests that flooded Moscow’s streets, watching as riot police beat up teenagers while wealthy Muscovites sipped Aperol on the restaurant terraces nearby. How are we going to play football tonight, Evan complained after one demo. His team’s best player had just been detained, thrown in a police van together with a bag full of their footballs.

The crushing of the opposition grew ever more methodical. Alexei Navalny’s office was raided so often that Evan wrote a piece about its front door, broken down so many times by police that it could barely close. “Kremlin Critic Navalny’s Front Door Has Had a Tough Year,” the headline went, rolling up the darkness and absurdity in one. Increasingly, Russian journalists — many of them Evan’s friends — also came face to face with the brute force of the state, labelled foreign agents, forced to flee.

Then, one evening in early February 2022, we met up to celebrate my birthday. As we made our way to the event, Evan read a report on the wires that Russia was moving blood supplies to the troops it had stationed around Ukraine’s borders. In that moment we realised that the darkness was about to close in completely, and soon enough it did.

Even after the Ukraine invasion began, Evan continued to report in Russia, convinced of his duty to tell a story that few others could. He took his first break from coverage a year later, when a few of us travelled to Vietnam. Evan lugged around a massive copy of Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate, reading long passages out loud. He’d picked the book as his beach read, he said, because it could help him better understand the war. I respected his commitment — on holiday I just wanted to switch off from the horror we had to absorb and report on every day. I bet he didn’t finish it, I thought, soon after he was detained.

We have quickly learnt how to support someone in jail. Among Russian journalists and activists there is a sad wealth of experience dealing with the country’s prison system, which is eerily digitalised. On a user-friendly interface we can order books to Lefortovo cells, arrange for magazine subscriptions and deliveries of food.

Ksenia Mironova, whose partner the Russian journalist Ivan Safronov is serving 22 years on treason charges, has taught us what we can and cannot post. She knows we can send Evan fresh fruit but not berries; cheese but not juice or eggs. I think of the sheer joy with which Evan — proud chef, proud raconteur of his time working in a New York kitchen — was just last month enthusing over the flavours of Vietnamese street food.

I’m in Berlin now. The S-Bahn roars and rattles, noisy pop tunes play from the kebab shops, but there’s a searing silence where our conversations with Evan used to be. Then, a letter back arrives. A short, handwritten note, and then another, his Russian scrawl getting ever neater. In his letters to friends, Evan makes jokes, describes tiny, amusing details about life in jail to cheer us up. “You all had a beautiful youth in Moscow, no one can take that away,” my mother wrote to him in a letter. “I’m still strolling around Moscow,” Evan replied, “just in one place for now.”

Today marks a month that Evan has spent in jail. He’s found his mammoth book in the prison library and has read it twice. I’ll make a start on it soon, we all will — something of an Evan book club. Its English translator, Robert Chandler, has also written to Evan. We’ve sent that letter, and we will send many more. Twenty roubles per page, 65 for the envelope, 75 more so he has the option to reply.

Readers are welcome to write to Evan at freegershkovich@gmail.com